Wolf advocates don’t often get to celebrate good news. But this week we do. First, we learned a litter of wolf pups were born this spring in Lassen National Forest. Then, we learned wolf pups were also caught on a trail cam in Oregon. Both litters are related to OR-7, the famous wolf known as Journey. He is a father for the fourth time and a grandfather for the first time. It is a modern family – and his incredible legacy continues.

OR-7 is the father of the Rogue Pack and lives in Oregon’s Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, north of Ashland. He was nicknamed Journey by schoolchildren for his epic journey across mountain passes, rivers and at least one interstate highway. He was the first wolf in western Oregon since 1947 and became the first wolf in California since 1924. His presence led wildlife advocates to push for Endangered Species Act protections for gray wolves in California – and today, though far from perfect, California has the most sensible, science-based protections for gray wolves of any state.

One of OR-7’s sons and his mate have settled in the Lassen region of California. That mate was recently captured, radio-collared and examined. From that capture, we learned she had given birth. Trail cams have now shown us these wolves, dubbed “the Lassen pair,” had four pups. They are the second set born in California in nearly a century.

The first, the Shasta Pack, made history when five black pups were born in Siskiyou County, California (north of Lassen and south of the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest in Oregon). The parents of the Shasta Pack were both descendants of the Imnaha Pack in Oregon, and are the siblings of OR-7.

But the entire family has vanished. Mostly, the family has been unseen since November 2015 when there was a “probable” (though not provable) depredation of a calf who could have died from a variety of causes. That month, there were vocal threats of violent reprisals from locals. Except for one pup seen in Nevada in late 2016, there have been no sightings, no scat, and no tracks of them confirmed since the threats made against them.

Many suspect scofflaw locals of employing the “Shoot, Shovel, Shut-up” approach, a popular strategy in these remote regions that allows people to violate the Endangered Species Act (for which they could otherwise face prison and penalties). We fear these killers have annihilated the entire wolf family – the first to make their home in California since 1924.

Something in me hopes we are simply wrong. The family is not radio-collared, and the price we pay for wildness is that we don’t always know where wolves are or how their story ends. In a way, it is a true sign of wildness.

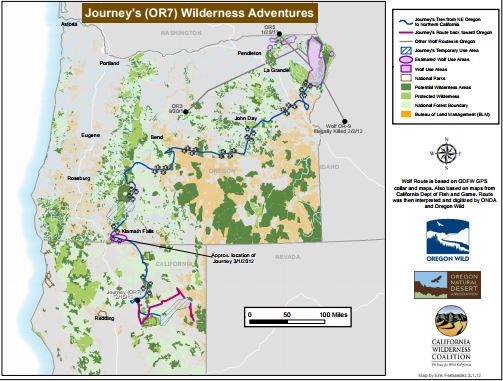

But Journey’s story is a legacy of wildness too and it begins in Northeast Oregon. Born in 2009 into the Imnaha Pack, he left his family at two years of age, presumably to find a mate. He had recently been collared by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, which tracked his travels. He wandered south west across Oregon and south east into the wilderness of northernmost California. These regions are sparsely populated and huge swathes of the land belong to the public, overseen by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS).

OR-7’s story has inspired people around the world, including a new generation fascinated by wilderness and the concept of the wild. The fact that OR-7 was in such breathtakingly beautiful territories – which are also laced with cattle that graze and destroy those lands and put wildlife in danger – inspired me to move to Siskiyou County in 2016, to the town of Mount Shasta (from which the Shasta Pack get their name).

There I learned firsthand what it’s like to live in these rural mountains, where many (including livestock operators) coexist with wildlife as suburban people coexist with human neighbors. But I also learned about a dark side, where some feel wildlife, like livestock, are here to serve our purposes. To them, when wild animals don’t suit human profits, it’s acceptable to destroy them – regardless of the ecological impact of doing so.

But wolves are important. Scientifically, the return of wolves is good for local ecosystems. Wolf pups are a sign we are heading toward recovery of a species virtually wiped out in the U.S.

Let’s not forget wolves are native wildlife, and cattle are an invasive nonnative species – their presence degrades the land and contributes enormously to global warming. And although some carry an irrational fear of wolves or concern about livestock-wildlife conflict, much of which is overblown, misunderstood, and rarer than portrayed, these conflicts can largely be avoided with responsible livestock management and training for livestock operators in nonlethal coexistence, which benefits our species, wild lands and canis lupus. It is proper livestock management, not wildlife management, with which we need to concern ourselves.

For me, it’s not just that he has left a legacy of wild wolves, or that his journey has defied all odds – at the age of 8 he is living a healthy life, despite being targeted by poachers – or even that his travels have helped reignite a movement for wolf protection in these parts.

My secret admiration also comes in the fact that he has eluded recapture. His collar batteries died in 2015, and while there is a valid reason for biologists to collar wolves with 5 pound telemetric radio collars, there are equally valid arguments not to. To me, he’s wild and free. And that’s how he should be. Our interest in where he is matters less than his right to be left alone.

We created an experiment when we reintroduced wolves to Yellowstone and the Frank Church Wilderness in Idaho. Gray wolves are now found in Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, California and beyond. A wolf named “Echo” even traveled so far as the Grand Canyon – 750 miles from where she was collared in Wyoming.

Echo traveled incredible distances to find a mate. She was killed in 2014 by a hunter who claimed he thought she was a coyote. That loophole in endangered species protections, called the McKittrick Policy, was used first after a man killed one of the most beloved wolves in Yellowstone. Two weeks ago, that disastrous loophole was closed. Still, the fight over the right of wolves to exist in their native lands is fraught and every forward step is a battle. But we take pleasure in each victory.

Journey, like Echo, has traveled incredible distances to find his home and make a family. He is perpetually in danger of being killed like his siblings and so many wolves before him. He is vulnerable to those who break the law, shun facts, and target endangered animals. Especially by those who would love to kill, rather than admire, a famous wolf.

We reintroduced wolves with the vision that they would be wild and free – free to love, to play, to roam, to inhabit those wild spaces that once were theirs. Journey’s story makes me smile because he has done just that.

Watch this beautiful documentary online about OR-7 and learn more about his story.